A story from

Ulster

The Goddess Fires of Candlemas

The Goddess Fires of Candlemas

by Jani Farrell-Roberts of

Ulster,

Raised with the rebel

songs by a mother

whose father was born on

Falls Road, Belfast.

(Footnote -also known as Jani Roberts, she uses here her

longer birth-name as it includes her maternal Irish ancestry)

Imbulc, or Candlemas, is the ancient feast of Brigit - so

what better way to celebrate the Goddess of Bards, than with a poem.

by Jani Farrell-Roberts of

Ulster,

Raised with the rebel

songs by a mother

whose father was born on

Falls Road, Belfast.

(Footnote -also known as Jani Roberts, she uses here her

longer birth-name as it includes her maternal Irish ancestry)

Imbulc, or Candlemas, is the ancient feast of Brigit - so

what better way to celebrate the Goddess of Bards, than with a poem.

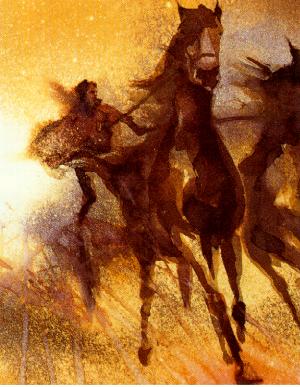

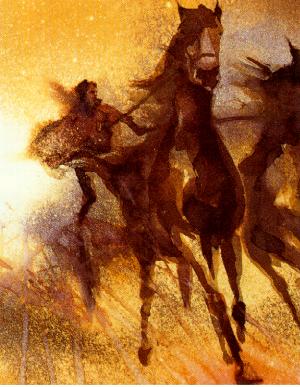

0 Macha,

1 Once it was written of you in

Ulster

2 that you were Grian - "the Sun

of Womenfolk".

3 Your spirit lived in hills and

moors

4 our rugged headlands, sweeping

shores.

5 Every feastday we would thank

you

6 for the harvest of mast that

fed us,

7 While you ran our

skies,

8 A White Mare Sun

Goddess

9 Few Stallions would dare mount.

0 Macha,

1 Once it was written of you in

Ulster

2 that you were Grian - "the Sun

of Womenfolk".

3 Your spirit lived in hills and

moors

4 our rugged headlands, sweeping

shores.

5 Every feastday we would thank

you

6 for the harvest of mast that

fed us,

7 While you ran our

skies,

8 A White Mare Sun

Goddess

9 Few Stallions would dare mount.

10 But then came the savage men,

eager to replace you,

11 who could not tolerate a

Goddess they could not tame,

12 who would not respect a

mother's pains.

13 Whose king at a Samhain

gathering,

14 challenged you to outrun his

horses,

15 thinking you would be slow

when pregnant.

16 Thus he set out to overthrow

the mother.

17

18 We share your pain as you were

forced to plead:

19 "Help me, for a mother bore

each one of you.

20 Give me King but a short delay

until I am delivered."

21 He would not delay for the

mother he thought defeated,

22 and so you cried: "My name and

the name of that which I will bear

23 shall forever cleave to this

place of Assembly for I am Macha".

24 And with that she out raced

the king's horses

25 before giving birth to

twins.

26 Then she cursed the men of

Ulster: "From this hour the shame

27 you inflicted on me rebounds

to each one of you.

28 When a time of oppression

falls upon you,

29 each one of you will be

overcome with weakness,

30 Like that of a woman in

childbirth,

31 and this will remain upon you

for five days and four nights,

32 to the ninth generation it

will be so."

33 And the cursed men still did

not respect the mother of all life,

34 they tried instead to curse

her by saying she was but the goddess of

their wars.

35 On days when Macha's gifts of

harvest were celebrated,

36 these savage men brought to

the feast

37 the heads of enemies, calling

these "the mast of Macha"

38 in savage mockery of her

harvest.

39 They claimed that life came

from the head not from the womb

40 And, holding severed heads

between their thighs,

41 Boasted gleefully they

possessed the source of life.

42 And the magic of the wombs

that bore them.

43 But when the time came for

Ulster to be oppressed,

44 When foreign princes rode

their northern necks,

45 Then Macha with her sisters as

the dreaded Morrigan

46 took care of the dead and

wounded from the fighting

47 and with magic fierce opposed

the wars of men

48 with all the power of the

threefold spiral.

49 While the men who feared the

Goddess sung

50 Of her taming and her rape at

the hands of brutish men.

51 So other forms the Threefold

took.

52 In the songs of Bard and

Druid,

53 Of Exalted Brigit they now

sung,

54 Fading the ancient image of

the Crow.

55 They spoke of her inspiring

Awen breath,

56 Of her as Mistress of poets,

of smithery and of healing

57 Thus they reshaped the triple

Goddess for an Ireland of high art,

58 Then with ancient strength,

renowned through Europe

59 As swift as the Fire Arrow

Breo-saigit,

60 She came against a triple God

of men

61 Who for Patrick was the only

source of magic.

62 Thus he fought her the serpent

mistress of high magic

63 Goddess of the fire tended by

priestesses

64 Where swords were banned from

beneath the sacred oak,

65 Where centuries after Patrick

death still burnt the fires of Brigit

66 Watched by "She who reversed

the streams of War"

67 In the sanctuary of Kildare,

Cill Dare, the Church of Oak

68 But Patrick's clergy also

served the women

69 For the Mothers used them

against the murderous kings

70 who in savage wars sought

female heads above all others.

71 Thus a mother, Smirgat of

Tara, bound Saint Adamnan.

72 Before another crumb he ate,

to seek the freedom of all women,

73 So with threat of curse

against the kings he freed the women

74 From kings but not his church

for he demanded in return that

75 Women pay his listed fees less

cursed be their children,

76 And thou' the churchmen

promised that Brigit as a saint would be honoured for all

time,

77 They hoped in God the Father's

name, we'd forget her divinity.

78 But in memory true at

Candlemas, with candles lit,

79 We honour still the fiery

course of Brigit,

80 And thus this ancient Imbulc

day

81 We invoke the Sun Mare

Goddess;

82 Our Crow, our Cow, our

Serpent

83 Our Brigit, our Morrigan, our

Macha.

84 Come oh never forgotten

Goddess

85 Come oh Fiery Sun,

86 Giver of heat and of

health

87 Chantress of our Sacred

Earth.

88 Breath your life into the

earth,

89 In Winter's Cold Dark we call

You,

90 Come oh Mare from the Night

bring Day,

91 We your people

call.

By Jani Farrell- Roberts - c98.

Notes on the Poem.

Over the ages our mental picture of the Goddess has

evolved to meet our changing needs - and in particular the changing

needs and status of womenfolk.

LINES 1-9

In the days of hunter-gathering and in the early days of

agriculture, the prevalent divine image seems to have been that of

the Goddess of fertility and of harvest. In Ulster this Goddess was

known as Macha. Macha was also the Sun, warming the earth, making it

fertile, bringing us our food ("mast" meant the food of both humans

and animals). In other places the Sun Goddess was known as Epona. In

this time the Goddess shone in her own right as the Sun, - and so too

did the women stand in their own right without need for men to give

them status.

(This for me is also reflected in the customs of the

hunter-gatherer Aboriginal Tribes of Central Australia, where I once

lived. There, in customs formed in similar economic circumstances to

those prevailing in the early days of Macha, women and men have their

own sacred laws and are of equal status.)

The kings of Ulster in what seem to be the oldest legends

had to honour the rights of women. They had to pledge that the

harvest (mast) should be provided every year, that there should be no

lack of supplies to the women cloth dyers and that no women should

die in child birth. Women could also be the ruler. A legend about

Macha of the Red Hair told how she defeated the king's son to become

the ruler herself.

The memory of Macha is still alive in Ulster. Armagh is

named after hills dedicated to the Goddess Macha. An image of Macha

is still preserved in its cathedral. Epona who was similarly imaged,

may be depicted in the images of a running white horse found cut in

the turf on English chalk hills

LINES 10-32

The story of how Macha outraced the King's horses then

cursed the men of Ulster is from an ancient Irish legend known as

"Pangs of the Men of Ulster." This is part of the preamble to

Ireland's epic saga the "Tain". This story arose around the time when

the ancient Goddess was being challenged in her role by the rising

class of warrior Celtic men. Macha demonstrates in it that she is

still supreme in speed, magic and skill but the very fact that a king

could force her to race shows that her position in society (and that

of women) was becoming weaker.

LINE 25 - 32

She was made to share some of her female knowledge with

men by being forced into giving birth in public. The curse suggests

that taking over female knowledge (and taking from the women the

respect they are due as mothers) will weaken the men. The time given

for men to feel weak is roughly equivalent to the length of a

menstruation period.

LINE 41-42

The male warriors now were collecting the severed heads of

enemies and would sleep with a head placed between their thighs in a

crude imitation of the role of a woman in childbirth - they may have

seen this as giving them than the power of the mothers.

LINES 45

Women often had to fight in the wars. They needed a

Goddess of the Battlefield as did the men (thus their talk of heads

being "the mast of Macha) - and so grew the myth of the Morrigan into

which the kinder harvest Goddess Macha was subsumed as part of a

triple Goddess with her two sisters, Badb and Morrigan. In Britain

she was probably Morgan. The Morrigan however came to be hated by men

who dreaded the female power she represented - so men tended to

depict her as a hag - or as three hags (perhaps as reflected in

Shakespeare's Macbeth).

LINE 46

But in the old sagas her role is much more that of the

healer of the wounded and of the taker of the spirits of the dead

into the next world. For example, Macha is depicted in these myths as

the Sacred Cow whose milk is an antidote to the poison of weapons.

She had become the Mother on the Battlefield.

LINE 47-48

The Morrigan does not normally use the normal war weapons

of which the Gods were so proud, but instead uses the powers of

magic. These powers were usually deployed to defeat the plans of the

men of war, to trick them into doing the will of the Goddess, to

demoralise the armies or to force an army to kill its own men. She

never fought alongside the men as far as I can see.

LINE 49-50

Irish myths of this period are full of accounts of

Goddesses that have been tamed - and even raped. The Goddess Tlachtga

was pack-raped by the three sons of a man she had gone to in order to

learn magic - and she then died giving birth to male warriors. The

Goddesses are described as the wives or sisters of Gods and as

inferior to these Gods. In one story Macha is demoted to being the

wife of Nemed and is powerless to prevent the slaughter that she has

foreseen. As part of the Morrigan she is of even lower status as a

daughter of the son of the god Neid rather than his consort. This

demotion probably went along with the lower social status of women at

this time. Some say women lost their status as mothers partly because

men had a great difficulty in coming to terms with their own

fertility. All women knew who were their own children - but the only

way for men to be certain of who were their children was to take away

the freedom of women to move around and love whom they will.

LINES 51-57

Brigit, or Brighid or Bride, then replaces the earlier

image of the triple Goddess of the battle field. This image is more

appropriate for an artistic society where Bards sung at courts. The

three aspects of Brigid are all known as Brigit . They are Brigit,

Goddess of Poets; Brigit , Goddess of Smithwork and Brigit, Goddess

of Healing.

LINE 58

Her fame becomes international - as needed by a more

interlocked international society - that has to defend itself against

more widespread dangers such as that posed by the legions of Rome.

The Brigantes of Gaul called themselves after her sons. Julius Caesar

called her the "Gaulish Minerva".

LINE 62

Brigit is not just the White Mare and Cow. She is also the

Crow, mistress of foretelling, and the Serpent. The Serpent with its

shedding of its skin, was for long a very sacred image signifying the

circle of life. When St Patrick is said to have driven all snakes

from island, this is a boast that he has driven from Ireland the

power of Brigit. (Likewise in England St George kills the

serpent-like dragon.)

LINES 63- 64

Brigit as the Sun Goddess was honoured at sanctuaries

where priestesses minded an everlasting flame. Brigit was also linked

to the oak - a Sacred Oak stood by the fire sanctuary.

LINE 64

The anti-war role of the Goddess continued at this

sanctuary. All weapons of war were banned from the vicinity of the

Sacred Oak. It also became a boast of the sanctuary that Brigit had

forced the dismantling of a nearby warlike centre Dun Ailinne

"Ailinn's proud citadel has perished along with its warlike hosts.

Great is the victorious Brigit"......

LINE 67

Brigit's fire sanctuary was in the City of Brigit now

renamed Kildare in honour of her sacred oak (from Cill Dara meaning

the Church of Oak ) Kildare remained a major spiritual centre for

centuries after the arrival of Christianity. From it Brigit was said

to rule the women, leaving the men to Patrick. Brigit was declared

the patron saint of Kildare while Patrick became that of Armagh.

Today there are many more places named after Brigit in Ireland than

there are named after Patrick.

LINE 65

After the rise of Christianity in Ireland, Brigid was even

said to have been made a Bishop - that is Christian monks in their

accounts of Irish history accorded her a rank that made her not a

Goddess but a priestess with power equal to that of the Christian

authorities. She was reported to be frequently visited by bishops and

to appoint the local bishop. This probably reflects the high power of

the Abbess and Nuns who seemingly took over the role of her high

priestess and priestesses (or who were the same women with a new

title). These stories of female bishops show that women in the name

of the Goddess had a higher sacred role here than in any other part

of Christianity.

LINE 65 to 67.

The Kildare nuns tended the everlasting flame of Brigit

while banning the sight of the flame from all men - as had Brigit's

priestesses. Their abbess also kept the ancient anti-war aspect of

the Goddess alive for among her titles was "She who turned back the

tide of war." It was only about 500 years later that the fall of the

Abbess from power was marked in the horrid ancient fashion also

suffered by Goddesses by her being raped by a soldier in 1132 to

render her unfit for office so she might be replaced by a woman

chosen by the local king.. But the fires of Brigit in Kildare carried

on being tended into the 13th Century. When in 1220 the Papal envoy

Henry of London ordered the extinction of the fire, the enraged

population forced the Bishop to order the relighting of the flames.

This was not long after the English pope Adrian IV had granted

Ireland to England.

Although the sanctuary and convent of Brigit at Kildare

survived until 1540-41 when Henry VIII closed the monasteries, images

of Christ's mother Mary showed her having a crushed serpent beneath

her feet - i.e. to have triumphed over Brigit and the old magic. But

in reality Mary took on aspects of Brigit and became the protective

female spirit to whom people liked to pray, asking her to intercede

for them with the all powerful and somewhat forbidding judgmental

God.

LINE 70

Female heads at one time were a favourite trophy for male

warriors. Some 7th century accounts depict the women as being forced

to battle as warriors for the kings. The initiation ritual for kings

of Ulster came to include the slaying of a white mare, the emblem of

Macha. The king had to bathe in and drink of the blood of this mare.

LINES 71-73

The status of women at this time was depicted in an

account of the 7th Century Saint Adamnan entitled Cain Adamnain (The

Law of Adamnan) in which pre-Christian and Christian beliefs are

melded and mothers are shown as powerful. In this story Ronnat, the

mother of Adamnan, tells him of his duties; "you should free women

for me from encounter, from camping, from fighting, from wounding,

from slaying, from the bondage of the cauldron." They go together to

view a battlefield where the bodies of women lie heaped. Ronnat

commands him to raise one of these from the dead. He raised Smirgat,

wife of the king of the Lunigni of Tara, who immediately binds him: "

Well now, Adamnan, to thee henceforward it is given to free the women

of the Western world. Neither drink nor food shall go into your mouth

until women have been freed by thee." His mother then, to make sure

he keeps this binding, puts a chain around his neck and a flintstone

in his mouth. When he still had not succeeded after 8 months he is

instead locked inside a chest. After several years of this, he is

freed and goes to the kings to free the women - who at first refuse

saying they will kill anyone who says that women should not be "in

everlasting bondage to the brink of Doom" But Adamnan instead

threatens the kings and gets his way.

But in return the Law of Adamnan lists the payments the

women must make to the church (LINE 75). Queens were to deliver

horses every three months and others tithes of harvest or of money.

If they failed to deliver, the saint threatened "the offspring ye

bear shall decay." In another story an angel instructs Adamnan to

establish a law in Ireland and Britain "for the sake of the mother of

each one." This echoes the plea made by Macha to the king of Ulster

because "a mother bore each one of you."

LINES 78 - 88

Brigit has had a long association with the festival of

Imbulc. On this day, the first of the Celtic spring, she was said to

"breathe life into the mouth of the dead winter." As the serpent

Goddess, she was also linked to the serpent. An old poem stated;

"Today is the day of Bride, The Serpent shall come from the hole." An

effigy of the serpent was often honoured in the ceremonies of this

day.

(Author's note - in this account I am greatly indebted to

Mary Condren for sharing her research in her highly recommendable

book : "The Serpent and the Goddess: Women religion and power in

Celtic Ireland", Harper Collins 1989.)

END

To Return to the

Introduction to the Craft of the Wise.

To

the Samhain version of the above poem

To Return to the

Introduction to the Craft of the Wise.

To

the Samhain version of the above poem

Click to return to the Library Entrance.

Click to return to the Library Entrance.

To Contact Jani Farrell-

Roberts

![]()

![]() Click to return to the Library Entrance.

Click to return to the Library Entrance.